Bayajidda: The Legendary Founder Of The Hausa People

Think of a hero who exists in both myth and history, similar to King Arthur or Romulus. For the Hausa people, that hero is Bayajidda – a legendary prince whose actions influenced one of West Africa’s most important cultures.

Key Points:

- Bayajidda is the legendary founder of the Hausa people, with stories mixing myth and history like King Arthur.

- His origins are unclear, with some saying he came from Baghdad and others from Yemen, similar to debates about other ancient heroes.

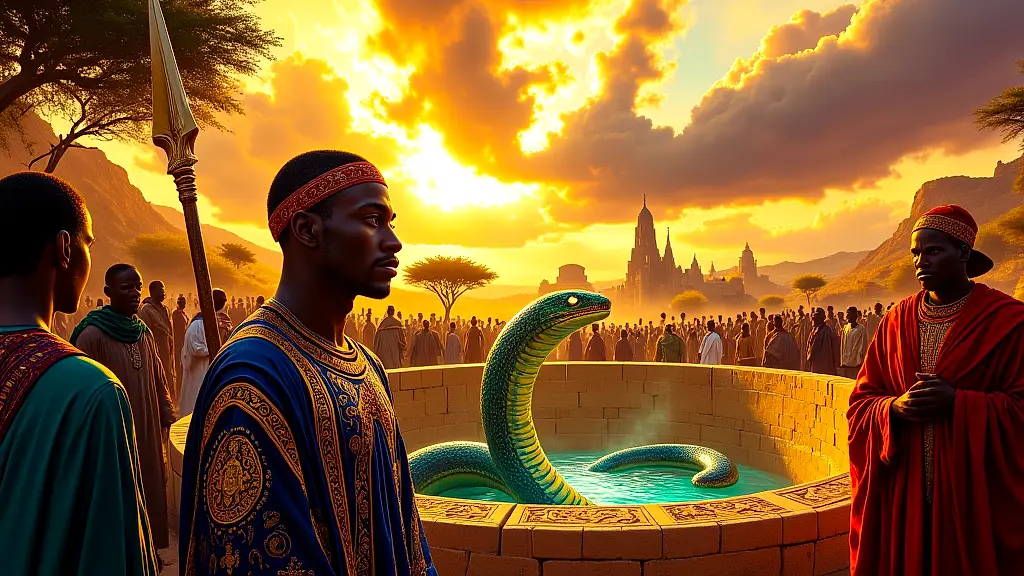

- The famous story tells how he killed a sacred snake at Daura’s well, which let him marry the queen and start the Hausa kingdoms.

- His seven sons with Queen Daurama founded the main Hausa city-states, while other lesser states came from different lines.

- The legend still matters today, seen in festivals like Hawan Daushe and how Hausa people see themselves as his descendants.

- Experts argue if he was real or just a symbol, but the story likely holds bits of truth about early Hausa history.

- His tale shares similarities with other African heroes like Sundiata Keita and Oduduwa, but mixes Islamic and local traditions in a unique way.

Scholars still argue whether he was a real ruler or just a symbol, but oral traditions like the Daura Chronicle all say he was the founder of the Hausa Bakwai (the “true seven” city-states). In this blog, we’ll explore Bayajidda’s mysterious origins, his fight with the sacred snake of Daura, and how his legacy defined Hausa identity.

Next, we’ll look at the different versions of his story (Was he from Baghdad or Yemen?) and compare his myth to other African heroes like Sundiata Keita. Let’s break down the legend together.

Bayajidda: Overview and Key Facts

| Category | Details | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Name and Title | Bayajidda (also spelled Bayajida or Abu Yazid); honored as the ancestor of the Hausa people. | Different traditions give him titles like Mai-duwatsu (“Master of Stones”). |

| Origins | Some stories say he was a prince from Baghdad, while others argue for Yemen. The Daura Chronicle supports Baghdad. | This debate resembles the one around King Arthur – where myth and history mix. |

| Symbols | Sword: Seen as a sign of power, similar to Excalibur. Horse: Represents nobility in Hausa culture. | His weapons play a big role in ceremonies. One example is the Hawan Daushe festival. |

| Key Myth | The Hissing Well: Bayajidda killed a sacred snake that scared Daura’s people, married the queen, and started a dynasty. | Some versions call it a dragon or water spirit. |

| Legacy | Father of the Hausa Bakwai (7 main states) and Banza Bakwai (7 lesser states). His descendants ruled Kano and Katsina. | Many ruling systems in these states connect back to him. |

| Cultural Impact | Festivals like Hawan Daushe recreate his story. His legend unites Hausa people across Nigeria, Niger, and other regions. | This is similar to how Oduduwa is seen in Yoruba culture. |

| Debates | Experts argue whether he was real or a mix of different leaders. There’s no archaeological proof, but oral stories stay strong. | It’s like the discussions about figures such as Robin Hood. |

Where Bayajidda Came From

No one knows exactly where Bayajidda came from. Now we’ll examine the different stories about his background that historians debate.

The Mystery of Bayajidda’s Birth

Different sources give different answers about Bayajidda’s origins. The Daura Chronicle states he was a prince from Baghdad who was forced to leave after fighting with his father. Meanwhile, others argue he came from Yemen, which makes sense because of language connections between Hausa and Arabic. This is similar to how people debate King Arthur’s birthplace – legendary figures often have multiple origin stories.

What makes it more interesting is that some versions include prophecies that predicted his coming to Hausaland. These stories share similar elements with other hero myths from around the world.

We know about these accounts from several key sources:

- Oral traditions kept by Hausa storytellers, which differ depending on the region

- The Daura Chronicle, a 19th-century document that combines history and legend

- The Kano Chronicle, which records his family line but doesn’t mention his early life

These discrepancies don’t mean the stories are wrong. Instead, they show how myths change to meet a culture’s needs. As we’ll see, the mystery only grows when we look at his journey to Daura.

Bayajidda’s origins are unclear, with some saying he came from Baghdad and others from Yemen, much like other legendary figures whose stories change over time.

Bayajidda’s Trip to Daura

Bayajidda’s journey to Daura was a difficult crossing of the harsh Sahara desert. After being forced to leave his home due to conflict (whether in Baghdad or Yemen as we’ve seen), he traveled west with just his horse and sword.

After traveling through challenging conditions, he arrived in Daura, in what is now northern Nigeria, as an exhausted stranger who needed water from the famous well. This led to his important meeting with the sacred snake. The two items Bayajidda carried – his sword and horse – hold deep cultural significance for the Hausa people.

His sword, sometimes called “Gajere” (meaning “short one”), was more than just a weapon – it represented royal power. The horse showed both travel ability and high status, linking Bayajidda to important trade routes across the Sahara. To this day, these symbols still appear in Hausa royal ceremonies, with swords and horsetails remaining key parts of traditional dress. Different oral histories describe this journey in various ways.

Some claim he traveled by himself, while others say he had company. The Daura Chronicle indicates he came through Borno, but other versions say he arrived directly from the north. All accounts agree this journey changed Bayajidda from an exiled prince into an important cultural figure – a common pattern in myths where heroes face challenges before achieving their purpose.

Bayajidda and the Famous Hissing Well

After coming to Daura as a stranger from elsewhere, Bayajidda encountered a crucial test at the town’s well known for its snake. This event would become pivotal in Hausa history.

Facing Off With the Sarki

When Bayajidda arrived, Daura was facing a serious problem caused by a mysterious snake that controlled the town’s only well. The Sarki (king) had ordered that water could only be taken once a week because the snake was dangerous. Bayajidda, being an outsider, either didn’t know about these rules or chose to ignore them.

His bold decision to approach the well became an important event in Hausa history. Different oral histories describe this event in various ways. Some show the Sarki as a good leader trying to protect his people, while others present him as a harsh ruler who used the snake to control water access. At the same time, Bayajidda’s reasons for going to the well range from basic thirst to following a spiritual calling.

| Version | Snake Description | Well Location | Decree Terms | Bayajidda’s Motivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daura Chronicle | Giant python | Market square | Complete ban | Prove his worth |

| Kano Oral Tradition | Medium serpent | City outskirts | Rationing | Quench thirst |

| Sokoto Variant | Shape-shifting spirit | Royal compound | Nobles-only access | Divine vision |

This story is interesting because it mixes real concerns about water access, which still matter in the Sahel region today, with magical aspects. The differences between versions show how oral traditions change stories to match what different communities value over time.

Killing the Sacred Snake

The snake Bayajidda fought was more than just dangerous – it was important in Daura’s early religion as a spiritual protector. When Bayajidda used his sword (some say during midday when the snake rested), this action meant several things. It showed a new power taking over, control of natural threats, and the end of the Sarki‘s spiritual control.

This type of story appears in other African traditions too. The Yoruba Aido-Hwedo, a giant snake that supports the earth, also represents ancient natural powers. Similarly, these snakes show wild forces that civilization must either defeat or balance. However, some versions of the story don’t completely praise Bayajidda’s act. They suggest that while killing the snake brought water, it also caused spiritual problems.

These different versions show how oral histories keep complicated views about people’s relationship with nature. Accounts vary widely about how the fight happened. Some say Bayajidda killed the snake with one sword strike, while others describe a three-day battle where the snake changed forms. Northern versions say he used magic spells learned during his exile, and eastern stories focus on his physical skill.

What all versions agree on is that this event changed Bayajidda from an outsider to a hero. It led to his marriage to Queen Daurama and the start of Hausa city-states. The well, once feared, became proof of Bayajidda’s right to rule.

How the Hausa Kingdoms Began

Bayajidda’s success at the well affected more than just Daura. It led to developments that changed the Hausa region’s politics for hundreds of years. After this, the story focuses on how his descendants created the famous seven Hausa states.

Bayajidda’s Seven Sons

The Hausa Bakwai (seven legitimate states) are central to Hausa historical traditions. According to the Kano Chronicle and other sources, Bayajidda’s sons with Queen Daurama founded these city-states:

- Daura – The original city, first ruled by Bayajidda

- Kano – Started by Bagauda, grew into an important trading city

- Katsina – Founded by Kumayo, became known for learning

- Zaria (Zazzau) – Created by Gunguma, later ruled by warrior queen Amina

- Gobir – Established by Duma, located in the northwest

- Rano – Founded by Bawuro, known for farming

- Biram – Started by Babari, completing the seven states

There were also the Banza Bakwai (seven illegitimate states), which included Kebbi, Zamfara, and Yauri. Oral traditions often describe these as rival or less important kingdoms. Although sources disagree on the exact list, this system shows the real competition between Hausa city-states. Each claimed they had the best connection to Bayajidda.

Historians believe these categories probably developed later to support their power claims, similar to how other royal families trace their history to famous ancestors.

Bayajidda’s Lasting Impact on Hausa Culture

The annual Hawan Daushe festival shows Bayajidda’s legacy in Daura. Horsemen recreate his arrival while the Magajiya, who protects traditions, leads rituals at the sacred well. At the same time, griots tell versions of the story that changed over 800 years. Bayajidda’s sword, sometimes displayed as an artifact, serves as a physical link to their history.

What started as local stories became an important cultural tradition, now including TV shows and museum displays that introduce the legend to new audiences. As Hausa people traveled through West Africa, the Bayajidda story became their shared origin story. Phrases like “Dan Bayajidda” (son of Bayajidda) became common ways to express Hausa identity. Later, when Islam spread in the 14th century, some versions changed Bayajidda into a Muslim prince.

This shows how the story adapted to stay important. Historians note this flexibility helped Hausa culture accept outside influences while keeping its own character. Modern Hausa artists often use Bayajidda in their work, from movies to music. During colonial times, British leaders sometimes changed the story to support their rule through local chiefs.

After Nigeria became independent, different areas used parts of the story to back their political claims. Through all these changes, the main parts – the outsider hero, the sacred well, and the seven kingdoms – stayed mostly the same. This proves how deeply the story matters to Hausa culture.

The Hawan Daushe festival keeps Bayajidda’s legend alive through horse rides, rituals at the sacred well, and griots telling his story, which has changed over centuries but still connects Hausa people to their shared roots.

Bayajidda in African Mythology

Bayajidda’s story extends beyond Hausa lands, sharing similar tales with other hero stories from Africa. When we compare his legend with other important early leaders, we see clear similarities. At the same time, important differences appear that make each tradition unique.

How Bayajidda Stacks Up to Other Heroes

When we compare Bayajidda to other West African heroes like Sundiata Keita and Oduduwa, we see common hero story elements with special Hausa features. Like Sundiata, who founded the Mali Empire, Bayajidda follows the classic story of a prince who returns from exile. The Yoruba’s Oduduwa, who came from the sky with sacred items, matches Bayajidda’s story about his special sword and unusual birth.

However, Sundiata’s story focuses on battles while Oduduwa’s involves creation stories. Bayajidda’s legend stands out because it includes both political beginnings and spiritual change through the well story.

All three stories share these key elements:

- Exiled Royalty – Each hero starts as a prince who had to leave home (Bayajidda from Baghdad/Yemen, Sundiata from Mali, Oduduwa from Mecca/the sky)

- Divine Weapons – Bayajidda’s sword, Sundiata’s magic bow, and Oduduwa’s creation beads

- Monster Slaying – Bayajidda killed a snake, Sundiata defeated the sorcerer-king Soumaoro, and Oduduwa fought early creatures

- City Founding – Bayajidda started Daura, Sundiata built Niani, and Oduduwa established Ile-Ife

- Cultural Legacy – All three became important cultural figures beyond their actual lives

What makes Bayajidda’s version special is how it mixes Islamic ideas with traditional Hausa beliefs. This combination appears less in Sundiata and Oduduwa’s stories, which mostly focus on local traditions.

Is Bayajidda Myth or History?

Experts disagree about whether Bayajidda really existed. Archaeologist Graham Connah notes that Daura was settled around the 9th-10th century CE, which matches parts of the story, but no proof confirms a specific founder. Historian Murray Last suggests the legend probably contains real information about migrations and political changes. Another important view comes from researchers like M.G.

Smith, who propose Bayajidda represents a combined story about several Hausa founders that later included Islamic ideas from trade across the Sahara. This debate relates to similar discussions about African history. Many oral traditions contain elements of truth through symbolic stories, though Western scholars first ignored these as just myths. The Bayajidda case shows how legends can hold historical value while still being important cultural stories.

Pantheon of Hausa Deities and Legends

Hausa mythology includes many spiritual beliefs that combine local traditions with Islamic influences. Among these are nature spirits called Iskoki (wind spirits) and the rain god Gajimari. If you want to learn more about similar African belief systems, check our complete list of all the African Gods. These beliefs show how cultures mixed in the Sahel region over centuries.

Traditional nature religions combined with Abrahamic faiths through trade across the Sahara. The Hausa spiritual world gives us a clear example of this cultural mixing that happened in West Africa.

FAQs

1. Was Bayajidda a real historical figure?

Bayajidda as a real historical figure remains debated, blending oral tradition with sparse archaeological evidence.

2. Why is the Hissing Well story central to his legend?

The Hissing Well story is central to his legend because it marks Bayajidda’s heroic triumph over the sacred snake, proving his divine right to establish the Hausa kingdoms.

3. How did Bayajidda influence Hausa governance?

Bayajidda influenced Hausa governance by establishing the Hausa Bakwai kingdoms, which became the model for centralized rule and dynastic succession in Hausaland.

4. Are there modern adaptations of his myths?

Modern adaptations of Bayajidda’s myths include contemporary retellings in literature, films, and cultural festivals like Hawan Daushe.