Satyr: The Half Man Half Goat In Greek Mythology Explained

Imagine a creature with a man’s upper body and goat legs. It has horns and is always drunk. That’s a satyr, one of the most famous hybrids in Greek mythology. These wild, lustful creatures caused chaos at Dionysus‘ parties. They were the center of attention, representing the uncontrolled natural world and the strong effect of wine.

Key Points:

- Satyrs are half-man, half-goat creatures from Greek myths, known for being wild, drunk, and causing chaos at Dionysus’ parties.

- They started as useless forest spirits in early stories but later became key followers of Dionysus, linked to wine and fertility.

- Their looks—human tops with goat legs and horns—meant wild nature and unchecked desires, often seen in art with exaggerated features.

- Romans turned them into calmer fauns, with human legs and ties to Faunus, losing much of their rowdy behavior.

- Famous satyr Marsyas challenged Apollo to a music contest, lost, and was skinned alive as punishment for daring to compete with a god.

- Pan, the only satyr who became a full god, ruled shepherds and wild places, causing panic with his sudden appearances and playing panpipes.

- Satyr plays mixed humor and wild antics in Greek theater, offering a funny break between serious tragedies at festivals.

However, satyrs were more than just party-goers in myths. Their history connects to older fertility cults, and their Roman versions, the fauns, were less aggressive. In this article, we’ll explore how they changed from Hesiod’s useless forest spirits to Dionysus’ followers. We’ll also look at their links to harvests and celebrations, and meet Marsyas, who made the mistake of challenging a god.

Whether you’re new to mythology or an expert, you’ll learn something new about these half-goat tricksters.

Half Man Half Goat In Greek Mythology: Overview and Key Facts

| Feature | Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomy | They had human torsos, often with beards, but goat legs, hooves, tails, and sometimes horns. Early art, like Minoan frescoes, showed differences, such as horse tails (silens). | They look like modern “devil” images, but they weren’t evil – just wild. |

| Behavior | They were wild, drunk, and always causing trouble. Dionysus, the wine god, kept them as his followers. Their actions showed uncontrolled nature and fertility. | Imagine them as the rowdy crowd at ancient festivals. |

| Divine Links | They mostly followed Dionysus, where they joined his wild parades (thiasoi). A few, like Silenus, were wiser but still loved wine. | Silenus was both smart and drunk, showing how wine brings creativity and chaos. |

| Symbolism | They stood for wild nature, strong sexuality, and good harvests. Art showed them with phallic symbols, linking them to fertility rituals. | They often appeared on wine cups (kylixes) during Dionysian celebrations. |

| Origins | They might have come from old fertility spirits. Hesiod’s Theogony called them useless forest creatures, but later myths made them Dionysus’ followers. | Some had horse features (silens), while others looked more like goats. |

| Roman Adaptation | Romans changed them into fauns, who were calmer, had human legs, and followed Faunus, a pastoral god. They were less sexual. | The differences are explained in the “Satyr vs. Faun” section. |

| Famous Myths | Marsyas lost a flute contest against Apollo and was punished. Silenus gave advice to Midas, and Pan loved Syrinx and Echo without success. | Marsyas’ story teaches the danger of challenging gods. |

Where Satyrs Came From and How They Changed

If you want to really know about satyrs, we should look at where they started. Their story goes from early pre-Greek spirits to Dionysus’ famous followers. We also need to see how they changed in different societies.

Early Stories Before the Greeks

Before the Greeks made satyrs famous as Dionysus’ wild followers, similar creatures existed in older Mediterranean cultures. We’ve found Bronze Age frescoes from Minoan Crete (around 1500 BCE) that show wild creatures with goat legs. Some call them Genii, and they held libation jugs, which means they were likely part of fertility rites. These figures might have inspired Greek satyrs, though experts aren’t sure if this connection was direct.

These were early versions. They focused more on crops and animals than on drunken behavior. Further east, artifacts from Mesopotamia and Anatolia show similar hybrid spirits. Examples include the bull-like kusarikku and Hittite gods resembling Silenus. While not identical to Greek satyrs, they shared animal legs and links to nature. This suggests many cultures were fascinated by human-beast mixes. But Greek satyrs were more mischievous.

Where Minoan Genii seriously made offerings, their Greek counterparts preferred wild parties with spilled wine.

Wild goat-legged creatures appeared in Minoan art long before Greek satyrs, possibly inspiring them but with a more serious role in fertility rituals.

Satyrs in Old Greek Writings

Hesiod’s Theogony (8th-7th century BCE) describes satyrs negatively. He calls them ‘good-for-nothing’ woodland creatures, more annoying than magical. Early writers showed them as simple nature spirits that lurked in forests and mountains, causing trouble without much purpose. But by the 6th century BCE, works like the Homeric Hymns transformed them into Dionysus’ loyal followers.

They changed from annoying creatures to becoming an important part of Dionysus’ celebrations.

Key appearances in Greek literature include:

- Hesiod’s Theogony: Calls satyrs “worthless” creatures born from earth (line 993)

- Homeric Hymn to Dionysus (7): Shows satyrs rescuing the young god from pirates

- Aeschylus’ Theoroi: Features satyrs as main characters in satyr plays

- Euripides’ Cyclops: Presents satyrs as funny, fearful but devoted creatures

As their role in literature changed, so did their religious significance. What began as unimportant woodland creatures became vital to Dionysian worship. Their wild behavior was now considered holy rather than just troublesome.

Romans Made Them Nicer: Meet the Fauns

When the Romans took Greek myths, they changed satyrs considerably. They turned them into more refined fauns – it was similar to changing wild party creatures into more civilized ones. The Roman versions kept the half-human form but altered their appearance. Instead of goat legs, they usually had human legs with some goat-like features. Not only that, but they also modified their famous crude behavior.

Romans linked them to Faunus, a nature god of forests and predictions. Greek satyrs represented wild parties, while fauns turned into timid forest musicians. Ovid’s Metamorphoses describes them as gentle spirits of nature. Virgil’s Georgics connects them to peaceful country life, which showed Roman values about farming. Even with these changes, they kept their ties to nature’s secrets.

What Satyrs Looked Like and What They Meant

After seeing where they came from, let’s look at how satyrs’ unique looks showed what they represented in Greek culture. Their half-human form wasn’t only decoration. In fact, each part had important meaning.

Goat Legs, Human Bodies, and Their Notorious Lust

The satyrs’ half-human form showed clearly how wild nature behaves. Their goat legs with hooves and tails stood for basic animal urges, while human torsos and faces showed recognizable expressions of desire. On Athenian vases from the 6th century BCE, these creatures often appear with obvious sexual features. Their goat legs were always bent as if ready to jump, appearing unable to control their passion.

Artists made this obvious. Satyrs displayed exactly what Greeks tried to control in themselves – wild sexuality, drunkenness, and forest-like freedom. Yet their human parts added depth. These weren’t simple animals but creatures who could play music, dance, and sometimes show wisdom, like Silenus.

The contrast between their goat halves and human tops demonstrated Greek worries about how easily civilization could lose to wild nature. A satyr on a wine cup reveals the Greeks’ hidden fears and desires – the uncontrolled side every proper citizen denied having.

Satyr vs. Faun: A Side-by-Side Look

Greek satyrs and Roman fauns come from similar roots, but their differences show what each culture thought about nature spirits. The table below shows key contrasts. You can see how the Romans basically changed satyrs to fit their culture:

| Feature | Satyr (Greek) | Faun (Roman) |

|---|---|---|

| Legs | Goat legs with hooves | Human legs (sometimes hairy) |

| Behavior | Lewd, rowdy, drunk | Shy, musical, pastoral |

| Divine Link | Dionysus (wine/grapes) | Faunus (forests/prophecy) |

| Symbolism | Uncontrolled desires | Rustic harmony |

| Art Depiction | Always ithyphallic | Rarely sexualized |

Greek satyrs usually appear causing trouble on wine cups, while you can see Roman fauns in garden mosaics playing panpipes. This shows how people changed the same creature to match different cultures. The biggest surprise? Satyrs preferred the loud aulos flute, but fauns chose the quieter panpipes.

Signs of Wild Parties and Good Harvests

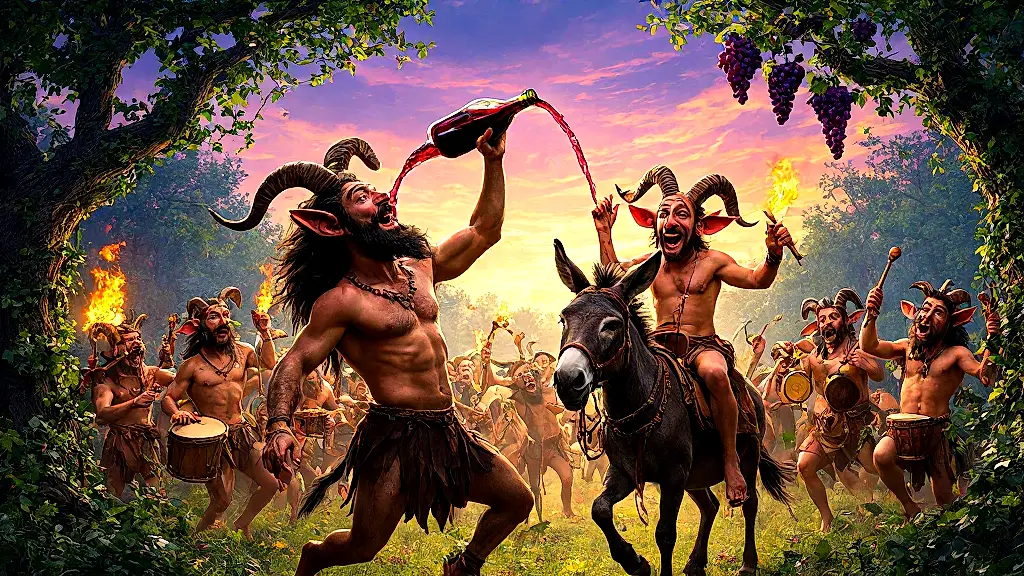

Satyrs were like the official party symbols in Greek culture. Their pictures on wine cups weren’t only decoration – these were ritual objects that turned regular drinking into a religious act honoring Dionysus. A 5th century kylix that shows satyrs stomping grapes wildly was like an ancient good harvest guaranteed sign. People believed their wild parties would ensure fertile vineyards.

These scenes often included sexual images, but not because Greeks were overly interested in sex. They saw a direct link between human fertility, crop growth, and the power represented by wine. Archaeologists found satyrs masks used in rural Dionysia festivals, which proves farmers acted like these spirits during planting and harvest times.

What made satyrs shocking in cities became important in farm fields. Their wild actions had spiritual meaning there. Athenian vases show their drunken behavior next to baskets full of fruit, which made the connection clear. There’s a reason why Dionysus’ main followers were these half-goat creatures: Greeks thought the same process that made wine ferment also made plants grow, and satyrs represented this powerful natural process.

Satyrs symbolized the wild but sacred link between human celebrations, fertile crops, and the natural power of wine in Greek religious life.

What Satyrs Did in Stories

Satyrs weren’t just symbols. They were active characters in Greek mythology, and their wild behavior created many stories. We’ll see how they changed from being artistic motifs to becoming important characters in myths.

Dionysus’ Party Crew

Think of the craziest party you’ve seen. Satyrs lived like that all the time as Dionysus’ constant companions. Ancient texts describe them as the god’s helpers who played loud music as they traveled. A vase from 480 BCE in the British Museum shows one pouring wine into his mouth while another rides a donkey, proving they showed what wild celebration looked like. Their crazy behavior had an important purpose.

As Dionysus’ team, satyrs tested whether people would join the religious ecstasy. When the god visited new places, his satyrs arrived first with music and wild actions. They worked like party starters, making people behave differently before Dionysus brought deeper changes. Archaeologists found proof these stories matched real rituals. At the Sanctuary of Dionysus in Athens, they discovered clay masks with big satyr features.

The satyrs’ constant drunkenness wasn’t just acting – it showed how worshippers needed to let go of normal behavior. While Dionysus often stayed calm, his satyrs made it clear that connecting with the divine meant breaking society’s rules.

The Sad Story of Marsyas

The story of Marsyas shows us one of mythology’s clearest lessons about not fighting gods. According to old writers like Herodotus, this talented satyr made a big mistake. He thought his aulos playing could match Apollo’s lyre – like a street musician thinking they could beat an opera singer. When the Muses judged their contest and Marsyas lost, Apollo gave him an unusually cruel punishment.

The god hung him from a tree and skinned him alive. Artists often showed this scene, and the Marsyas River in Phrygia flowed where people said his tears or blood fell.

This story is interesting because it reveals important Greek ideas:

- Instrument Rivalry: The aulos meant wild emotion, while the lyre stood for control

- Divine Punishment: Apollo’s harsh penalty showed how Greeks believed gods kept order

- Mortal Limits: Even a special creature like Marsyas had limits

Different versions exist. Some say Athena cursed the aulos after throwing it away, while others claim Marsyas just found it. But all agree on the main point: no one should challenge the gods. On Greek vases, artists often show Apollo adjusting his lyre while Marsyas suffers nearby. Today, the river (called Çine Creek in Turkey) still flows, showing how seriously the Greeks took these warnings.

Pan: The Almost-God Satyr

Pan was special among Greek gods as the only satyr who became a full god, though he always stayed different on Olympus. While normal satyrs followed Dionysus, this horned, goat-legged god watched over shepherds, animals, and wild places.

Most people know the word ‘panic,’ which comes from the fear Pan caused when he scared travelers, though he also played calm music on his syrinx (pan pipes). These magical pipes came from his failed chase after the nymph Syrinx, who turned into marsh plants to escape him – a story Ovid tells in his Metamorphoses. Pan was interesting because he existed between gods and animals.

Other gods lived in glory on Olympus, but Pan liked hiding in caves and woods, so people both respected and somewhat feared him. Greeks showed him differently than regular satyrs: where normal ones looked horse-like, Pan always had goat features, which included curling horns and a constant erection.

He even helped in important events, like supposedly aiding the Athenians at Marathon, proving this wild god could help humans despite his nature. Different areas worshipped Pan in their own ways – Arcadians saw him as an ancient god, while Athenians thought of him as a rough but helpful protector.

Silenus: The Drunk Who Knew Everything

Silenus was a strange combination of drunk and wise – an always-intoxicated satyr who knew hidden truths. As Dionysus’ teacher and companion, his big belly and red face hid surprising special knowledge. Ancient writers say he stayed so drunk that other satyrs had to hold him up or put him on a donkey, yet when properly drunk, he might reveal deep truths.

This contradiction made him an unreliable but sometimes insightful oracle – getting advice from him was like listening to a brilliant but always-drunk professor. His most famous moment came with King Midas, when the king’s servants found him passed out in a rose garden and captured him.

According to Aristotle, Silenus said the best human fate was never being born, and the next best was dying young – a dark philosophy that a drunk satyr expressed. This shows his role in Greek thinking: he spoke truths when drunk rather than when sober, similar to how Dionysus’ wine could both enlighten and harm.

Different ancient writers like Theognis and Virgil showed Silenus in various ways – sometimes as a fool, other times as knowing secrets – but always keeping this mix of looking foolish while being wise.

Satyrs in Art and Plays

Satyrs were perfect for Greek artists and playwrights because of their wild antics and distinctive forms.

The Funny Plays About Satyrs

Athenians would watch three serious tragedies, then enjoy a wild, funny break with satyr plays during Dionysian festivals. Troupes wore exaggerated leather phalluses and shaggy costumes while performing these unique shows.

The only complete surviving example is Euripides’ Cyclops, which takes the myth of Odysseus and shows it through the drunken view of Silenus and his satyr chorus – mixing humor and wild behavior in a unique way. Actors performed athletic sikinnis dances while telling crude jokes, with aulos (double flute) music keeping the fast pace that made audiences laugh. These plays combined religious meaning with pure fun.

While tragedies dealt with deep suffering, satyr plays celebrated wine and wild behavior in honor of Dionysus. In Sophocles’ Ichneutae, satyrs track stolen cattle but panic when they hear music for the first time. Vase paintings show performers with padded bellies and horse tails, their masks fixed in comic expressions.

Though we only have fragments of about 30 plays, Aristotle’s Poetics confirms they were their own special type of drama – not quite comedy or tragedy, but something truly Dionysian.

Satyr plays gave audiences a funny, rowdy break from serious tragedies, mixing wild humor with religious celebration of Dionysus through crude jokes, lively dances, and exaggerated costumes.

Famous Art of Satyrs

Satyrs appeared frequently in Greek art, from small cups to temple decorations, always showing their typical grinning faces and exaggerated features. Some important examples include:

- The François Vase (570 BCE): This large mixing vase depicts Dionysian processions. Satyrs appear in the second section carrying wineskins and playing music, with clear horse-like ears and tails.

- Praxiteles’ Resting Satyr (4th century BCE): This important statue, which we know from Roman copies, shows a more elegant satyr leaning against a tree. The original bronze looked so real people thought it might move.

- The Satyr and Maenad Cup by Makron (490-480 BCE): This red-figure kylix in Munich captures a satyr chasing a maenad, with his exaggerated features showing typical Dionysian behavior.

- Pergamon Altar Satyrs (2nd century BCE): These carvings from the Hellenistic period give satyrs more goat-like features, demonstrating the interest in realistic bodies during fights with Giants.

FAQs

1. Are satyrs and fauns the same?

Satyrs and fauns differ as Greek chaotic, goat-legged followers of Dionysus versus Roman gentler, human-legged spirits linked to Faunus.

2. Did satyrs ever interact with heroes like Hercules?

Satyrs interacting with heroes is documented in myths like Hercules capturing the satyr Silenus.

3. Were satyrs considered dangerous?

Satyrs were considered dangerous due to their unpredictable, lustful nature and tendency to disrupt order, though they were often portrayed humorously in myths.

4. Do other mythologies have satyr-like beings?

Satyr-like beings appear in other mythologies, such as Norse goat-legged spirits, but remain most iconic in Greek lore.